Ep 4 | Did Jesus Rise From the Dead?

| September 27, 2013 |

Introduction

Today we invite you to hear a debate between one of the world’s foremost philosophical atheists, Dr. Antony Flew, former professor at Oxford University, and Christian philosopher and historian Dr. Gary Habermas, current chairman of the Department of Philosophy at Liberty University, on the topic “Did Jesus Rise from the Dead?”

- Dr. Antony Flew: For a person like myself confronted with an apparent miracle, the rational thing is to think that there must be some mistake here. Though I could be persuaded that a miracle occurred, it would need something really very spectacular.

- Dr. Gary Habermas: Probably the single most important fact is that the disciples had experiences that they believed were appearances of the risen Jesus.

- Dr. John Ankerberg: “The disciples had experiences which they believed were literal appearances of the risen Jesus.” Well, obviously, you’re taking that in a naturalistic way. So give me your theory, how did that happen? I mean, something happened, is what everybody is saying.

- Flew: I take it these were grief-related visions and there was nothing there that anybody else could have seen.

- Ankerberg: What do you think, Gary?

- Habermas: I think Tony is getting himself in a lot of hot water. Number one, he’s got an empty tomb with no cause ventured for the tomb. Secondly, he’s got hallucinations for the disciples that don’t work for the half dozen reasons I gave earlier: groups don’t see hallucinations; they weren’t in the right frame of mind. You have different times, places, people, gender, doing different things. The empty tomb, it doesn’t transform lives. James, Paul. All reasons.

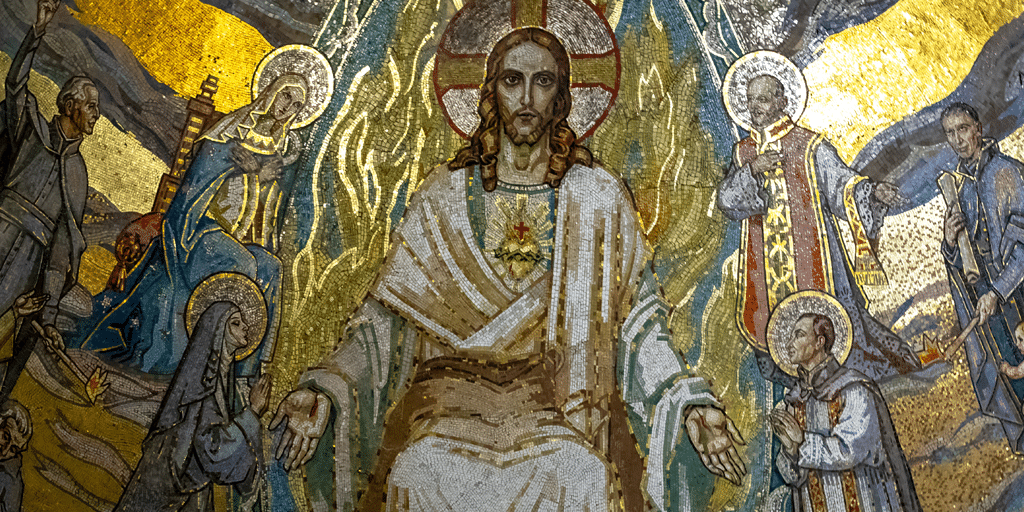

Christianity stands or falls on Christ’s resurrection. If Christ has risen from the dead, then Christianity is true. If He did not, then Christianity is false. Even the apostle Paul wrote, “If Christ has not been raised, then your faith is groundless, your preaching is useless, and you are still in your sins.” We invite you to join us for this important debate on The John Ankerberg Show.

- Ankerberg: We’re talking with two world class philosophers here and I think everybody that’s taken a graduate course in philosophy, they know Dr. Antony Flew. He’s one of the world’s foremost philosophical atheists. And Dr. Gary Habermas, a renowned Christian philosopher and historian, considered by many to be the foremost expert on the evidence for Jesus’ resurrection.

- We’re talking about the question: Did Jesus rise from the dead? And what’s the evidence? Is there any evidence? And one of the key things, gentlemen, that we’ve got to talk about is what did happen to this fellow by the name of Paul that was out there killing Christians, going after them. He wasn’t in the frame of mind to believe; didn’t want to believe, thought they were dead wrong. And all of a sudden, he became one of the greatest propagators of the Christian faith. Now, something happened. Tony, talk to me. What do you think happened to Paul?

- Flew: Well, the account seems to be that he had some companions, the people who later after he had unfortunately temporarily lost his sight and took him on in to Damascus. And he thought that the risen Jesus, the Christ, the Messiah, he had seen this and the Messiah talked to him. But his companions, apparently, most heard… on some accounts he heard a voice and some they didn’t. But they certainly are not said to have seen something that you could push around, any sort of ordinary or even abnormal human body.

- Ankerberg: Alright. So Gary, what do you say to your buddy?

- Habermas: Well, again, I think the main problem with Paul, he’s right. The crux of the data is that we have Paul himself on several occasions – 1 Corinthians 9:1; 1 Corinthians 15:8; Galatians 1 – saying he saw Jesus. But I don’t think he’s a candidate for Kent’s theory, not a candidate for “conversion disorder,” because like I said, conversion disorder does not involve hallucination. So Paul would have to have a conversion disorder; number two, an auditory hallucination because he thought he heard a voice; three, a visual hallucination; four, and then a messiah complex – visions of grandeur, so to speak, because he believed God spoke to him and gave him a message for the whole world; and five, there’s not one speck of evidence from Paul’s account that he was in the mood to be changed, why he would want to change.

- So it seems to me, we have four psychological problems and then a biblical problem from Paul’s writing. I’m wondering how you can change a conversion disorder of Kent – your theory – how you can change or combine, let’s say, a conversion disorder with a visual hallucination with an auditory hallucination with visions of grandeur messiah complex. And this all happened at once.

- Flew: Most of the time I’m not trying to offer a naturalistic or any other explanation. I want to know what the alleged phenomena are here….

- Habermas: But that is a naturalistic theory.

- Flew: Well, it is a possible one. There may be something wrong with that. I don’t profess to be a psychological expert who knows what a conversion disorder is. I have read William James and so on.

- Habermas: I’m just saying it doesn’t even follow. Even if he had a conversion disorder, it doesn’t follow that he would see, hear, and think God gave him a message.

- Flew: Oh, no. Okay. These are reasons for not accepting conversion disorder as an explanation. I’m not particularly worried about that. I mean, I read this in Kent’s….

- Habermas: You’re not giving it up.

- Flew: No. What I want to raise is what it was that Paul actually saw. What he thought he saw was the risen Christ. But what was there to be seen and his companions apparently didn’t see the risen Christ or anything else other than Paul obviously having some very important transforming experience.

- Habermas: If you take the texts in Acts, Acts 9:22 and 26, they did see a light. The companions did see a light. They all fell down on their knees. They heard a voice but they didn’t understand what the voice was saying. So I don’t want people to get the idea that what I’m agreeing with you on is that they were just standing there and they saw nothing. They saw light; they heard a voice; they fell down to the ground. So plainly there’s an objective affect on them, too, which, by the way, is an additional problem for conversion disorder. Because if Paul has a conversion disorder, how come his companions are falling down to the ground, seeing a light, and hearing a voice?

- Flew: Okay. Okay. Okay. I never professed to be a psychological expert. Okay, conversion disorder won’t do. But still, in order to have something that is going to transform your life,…

- Habermas: That’s right.

- Flew: This is, of course, entirely agreed. This is absolutely crucial. But unless there was something there that the television cameras could have picked up and all that, we don’t have any reason for thinking that, you know, other than if we already have reasons for believing that God’s going to communicate with Paul.

- Habermas: You’ve got Philippians 3; you’ve got those three arguments in Philippians 3 that Paul thought this was a physical body.

- Flew: Yes. Okay. He thought that, but….

- Habermas: That’s right.

- Flew: But the fact that he thought that is not a reason for being decisive in saying that it was there.

- Habermas: Yes, but I mean, when you said Paul believed in a spiritual, sort of a ghostly appearance of Jesus, Paul is very clear that what appeared is a body. So he must have thought he saw a body, and if you like the Acts accounts, you still have the three companions falling down, seeing a light, and hearing a voice. And that’s not a conversion disorder. Are you giving up the conversion disorder?

- Flew: I don’t care. I’m quite happy to give it up. I’ve never really been devoted to this. The thing I want to maintain is, there wasn’t anything there to be seen. How he came to have that, you know, this is the business of psychologists of which, thankfully, I’m not one.

- Habermas: If it’s not a conversion disorder, I’ll just turn the question around to you. If it’s not a conversion disorder, and he did not see Jesus, then what did he and his companions see? Why did they all fall down together? What happened on the way to Damascus? If it’s not a hallucination and it’s not a resurrection, then what is it?

- Flew: If it wasn’t visible to his companions, then it can’t have been a physical body.

- Habermas: Who said it wasn’t visible to the companions. I mean, they see a light; they fall down; they hear a voice.

- Flew: That’s all we’re told….

- Habermas: Let me put it this way. Philosophically, as you know, a contradiction, two things cannot both be and not be, same time, same place, same manner. We’re told what they saw but we’re not told what they didn’t see. There could have been a physical body standing right there. We’re not told there was no body. The text nowhere says there was no body here. And then in Philippians 3 Paul says He’s a body. The only data we have is Paul’s, right? We don’t have the companions.

- Flew: Yes.

- Habermas: We only have Paul’s and Paul seems to think it was a physical body. So at least, here’s the problem. One of our four facts: Paul believes he saw an appearance of the risen Jesus. If it’s not a hallucination, where do we go?

- Flew: But this is what virtually all the people in the Gospels who saw the risen Christ seemed to have thought, you know. The only cases of them actually poking and trying to see whether it was tangible are a very small group compared with all the others.

- Ankerberg: Alright, let’s hold on and let’s talk about that other small group when we come right back. What about the others that we’re mentioning. What happened to them? We’ll talk about it in just a moment.

- Ankerberg: Alright, we’re back. And we’re talking with Dr. Antony Flew, considered to be by many the world’s foremost philosophical atheist; Dr. Gary Habermas, renowned Christian philosopher and historian, considered by many to be the foremost expert on the evidence for Jesus’ resurrection. They’re going at it here. And we’re talking about did Jesus actually rise from the dead? If so, what kind of body did He rise in? And that’s where we’re at right now. What did the disciples see? And we talked about Paul. You’ve still got Peter; you’ve got James; you’ve got Thomas; you’ve got the women. You’ve got all the others that are mentioned. Where would you like to start?

- Habermas: Well, he introduced the case of the women touching Jesus in Matthew; Mary touching Jesus alone in John; and Thomas at least close enough that he could have and later, Ignatius says he did. I’d ask the same question: Are the disciples good candidates for hallucination or did they touch somebody who seemed to be Jesus? We have the hallucination theory again.

- Flew: Well, they are the cases where there’s a claim of tangibility; a minority of the total cases.

- Habermas: How many times do you have to touch somebody for them to occupy time and space?

- Flew: Not very many.

- Habermas: Once would do it, right?

- Flew: Oh, yes. But the point is, what’s the minority is the cases of people who are mentioned as having seen the risen Jesus of whom we are also told that they did something to verify whether there was an object there to be seen.

- Habermas: Of course, now, somebody wouldn’t have to touch Jesus.

- Flew: Oh, no.

- Habermas: You can be objectively present in this room and me never touch you.

- Flew: Oh, yes.

- Habermas: So, we have the women touching Jesus; Mary touching Jesus; you have Thomas given the opportunity to touch if you like the Gospels, again. But even Paul’s accounts, again, we’ve got Philippians 3. If Paul’s thought is that Jesus appeared physically, at least that’s Paul’s conviction. So it seems to me, again, you have the two horns of the dilemma again. With the disciples, you’ve either got hallucinations because they believed they saw something. Kent says Habermas’ facts are okay but I think it’s a hallucination. Do you still like hallucinations for the disciples?

- Flew: I’m not sure about what labels apply. What seems to me is the crucial thing is whether there was something there to be seen, hallucinated or whatnot, not whether you call it a hallucination or a vision or whatnot. The crucial thing is whether there was something there to be seen. And it seems to me the evidence for that is pretty weak really.

- Habermas: You’ve got the disciples saying Paul and the others had experiences that they believed were appearances of the risen Jesus. Okay?

- Flew: Yes.

- Habermas: You’ve got a tomb that’s empty. So something physical is going on. Only some of the texts claim they touched Jesus. This all points in the direction to a body being there. They know this person. They’ve been with Him for three years. He’s their best friend. In some cases He’s their relative: He’s their brother; He’s their son. Where can we go from here? You still have to take hallucination, right?

- Flew: They were said to have been, for instance, walking along with Him for some time without apparently noticing He is the risen Christ.

- Habermas: That’s a good point and I haven’t seen you for 15 years and I recognized you in the hotel yesterday. But there were changes and there were changes for me after 15 years. I mean, if there are slight, subtle changes in the resurrection body – which I think there are – that’s all you need. You know how you look at somebody and you look back and you say, “Is that you?” I think the fact that Paul does say “spiritual body.” I think it’s a literal body, and I think it occupies space and time and could be touched. But there are changes. So I think that accounts for the fact that He looked just a little different.

- Ankerberg: Can I throw in, too, the fact that I think it’s always fascinating that you have another skeptic, a very tough skeptic during Jesus’ own life, His brother, who actually at one time implied Jesus ought to go up to Jerusalem and get Himself killed, in a sort of sarcastic way. And all of a sudden this boy ends up as the head of the Church in Jerusalem. Now, he didn’t believe in Jesus the whole time Jesus was living. What happened to James, Tony?

- Flew: Don’t know. Why am I expected to know? Why is anyone expected to know what went on in Jerusalem at an unknown date?

- Ankerberg: I think it’s like going into court and saying to Habermas, “Except for your ten witnesses, you’ve got nothing, Habermas!”

- Flew: Oh, no. I think he’s got a lot. I think he’s got a rather few of these people clearly reporting that they saw something that was there and took some steps to discover whether it really was. Thomas is a rather curious minor figure among all these people seeing the resurrected…

- Habermas: You like him, don’t you.

- Flew: Yes, I do, because he seems to me to be doing the thing that virtually anyone with any skeptical inclination at all would do right away.

- Habermas: I think where John’s going is, this is just a part of the multifaceted nature of the resurrection evidence. You’ve got a group of women. You’ve got a lone woman, Mary Magdalene. You’ve got a group of men. You’ve got a lone man, James, who in 1 Corinthians 15:7 we’ve got Paul’s testimony about James. Now James is no longer a skeptic. He believes he sees Jesus. You’ve got Paul. And you’ve got an empty tomb.

- And we’ve got one strand after another after another. And that’s why I think Christians say we have a lot of evidences that come in. And just about the time the skeptic says, “Well, what about this?” you say, “But what about Paul? What about James?” The evidence comes in from a variety of aspects. And you know, as a historian, that’s what a historian wants. A historian wants a lot of evidence coming in from different angles: from enemies, from believers, you’ve got two skeptics who were enemies. You’ve got the Jews admitting the tomb was empty. You’ve got women who are not supposed to be good witnesses and they’re seeing Jesus at the tomb and grabbing Him. I mean, there’s a lot of data here, and that’s why I think Christians are Christians, because this is the key fact in the Christian faith.

- Flew: Well, I think it’s worth going back to the thing I said earlier on that how you rationally respond to these things depends very much on what your previous beliefs were. And if your previous beliefs were Jewish beliefs, believing in the coming of a Messiah and so on deriving from the Mosaic theist tradition, then it seems to me all this sort of thing becomes for you very reasonably persuasive.

- Ankerberg: But the thing that wasn’t persuasive for those guys is that this fellow also claimed to be the Son of God. Now, Kent in his book said Paul never said anywhere in the New Testament that Jesus was God. I would challenge Habermas. The critics say, you know, “Show me where Jesus claimed to be God.” You’ve got five strands of data that you can go to and Jesus shows up saying He’s the Son of God, Son of Man in all five strands. Do you want to go that direction?

- Habermas: Yes. I think we have both. I think we very clearly have Paul saying he believed Jesus was the Son of God. But here I would say we’ve got data that predates Paul. A huge question today is what was Jesus’ messianic self-consciousness, or as we’d say today in the West, who did He think He was? And what critics do here is, they don’t like the Gospels as much as they like Paul, as we’ve said several times. Paul’s evidence is the best, but they do like passages in the Gospels that meet certain critical criteria. And in several of those passages, you’ve got Jesus claiming to be either the Son of God or the Son of Man. And I would just say as a footnote, “Son of Man” was Jesus’ favorite title for Himself, but His usage of it is apparently taken from Daniel 7:13-14. He virtually quotes Daniel 7:13-14 twice when He stands before the high priest.

- Now, here’s an example. You have to have a reason He dies. Why did the Romans do what they did? Why did the Jews want the Romans to do it? In Mark 14:61-64 the high priest says, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed One?” Now, notice, the question, “Are you the Son of God?” Jesus responds in the Greek, Ego Eimi. His first comment is, “I am.” Secondly, He changed a Son of God question to a Son of Man answer. He said, “Henceforth you will see the Son of Man coming in the clouds of heaven and He is going to judge you.”

- Now, the high priest should have said, “Oh, no. You said Son of Man. I asked for a Son of God….” No. He knows right away when Jesus says, “Son of Man,” that’s a claim to be deity. And by the way, that phrase, 5“coming with the clouds,” that phrase occurs dozens of times in Scripture and is always a reference to God. So Jesus says, “Yes, I am” to Son of God. He says, “I am the Son of Man. I’m going to come in judgment.” And at that point the high priest says, “All the rest of you witnesses can go home. We’ve gotcha.” He said blasphemy. So, there’s an example.

- You have the so-called “Q” sayings, statements that are in Matthew and Luke but are not in Mark. And whatever you call that, they’re in the Gospels. In one of those passages, Matthew 11:27 and its parallel in Luke, [Luke 10:22] Jesus says, “No one knows the Son but the Father and no one knows the Father but the Son and those to whom He will reveal them.” Mark 13:32, He claims to be the Son of Man. And the reason critics find this very hard to explain away, again, it’s what historians call the principle of embarrassment. Jesus says, “That day or hour knows no one except the Father, not even the Son.”

- Now, if you’re claiming to be the Son of Man, why do you say you don’t know something? That’s embarrassing. As one British theologian says, “If the Church were just trying to make Jesus say He is the Son of Man, well just have Him say it. Don’t make up this problem about He doesn’t know the time of His coming.” But in that passage He calls Himself the Son of Man.

- So these are some of the senses that Jesus seemed to have thought of Himself as deity. And Paul clearly calls Jesus deity. He calls Him God on a few occasions and his two favorite titles are Lord and Christ. And I’ll just say real quickly, Lord, in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament, Lord is the translation of Jehovah. So Paul, who quotes the Septuagint, has got to know that and He calls Jesus “Lord” repeatedly.

- Ankerberg: We’re out of time. Wrap this up and then we want to come to Tony in the next segment in terms of the overall package that we’re talking about. Is it sufficient evidence to persuade a skeptic? Okay? But wrap this up where you’re at here in terms of, I think “Son of God,” “Son of Man,” if it’s there, and you have a resurrection, you put those two together, here’s what?

- Habermas: Well, yes. I think you have some authentic verses that even critics appreciate where Jesus calls Himself the Son of God. You’ve got some authentic verses where He calls Himself the Son of Man. Paul’s earliest witness, he calls Jesus Son of God, he calls Him Lord, he calls Him Christ. By the way, Romans 1:3-4 Paul says the resurrection proves all these things. So that’s your point you just raised a moment ago. Yes, in the New Testament the resurrection is God’s stamp of approval on who Jesus thought He was. Now, I mean, in our 1985 debate, Tony made the comment that if Jesus was raised from the dead, this is the best evidence that He is the God of Abraham, Isaac and Israel. I think it’s pretty close to a quote. Of course, he doesn’t believe in the resurrection, but I’m saying, if the resurrection occurred, that’s why people think Jesus is the Son of God because only God, the presumption is, only God can raise the dead and if He raises this man, He can’t be a heretic. What He said about Himself must be true.

- Ankerberg: Alright. Next week my guests will discuss: How much evidence is needed to intellectually pull a skeptic over the line to believing Jesus rose from the dead? For example, I’m sure you’ve attended many funerals. How many of those people ever came back from the dead? None. Well, if all of our experience informs us that dead people stay dead, how could we ever gather enough evidence to believe Jesus conquered death? These are the questions my two guests will debate next week. I hope you’ll join us then.